Fažana, a small fishing town in southern Istria, has been characterized throughout history by various forms of industry. Since ancient times it has been recognized for its wine making (enology), olive-growing and fishing. However, Fažana’s industry began to boom in the late nineteenth century, continuing to develop throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and culminating during socialism. At that time, the industry also became part of Fažana’s identity, mainly because of the liquor and soft drinks factory Badel Fažana, whose workforce mainly consisted of women from Fažana and the surrounding area.[1]

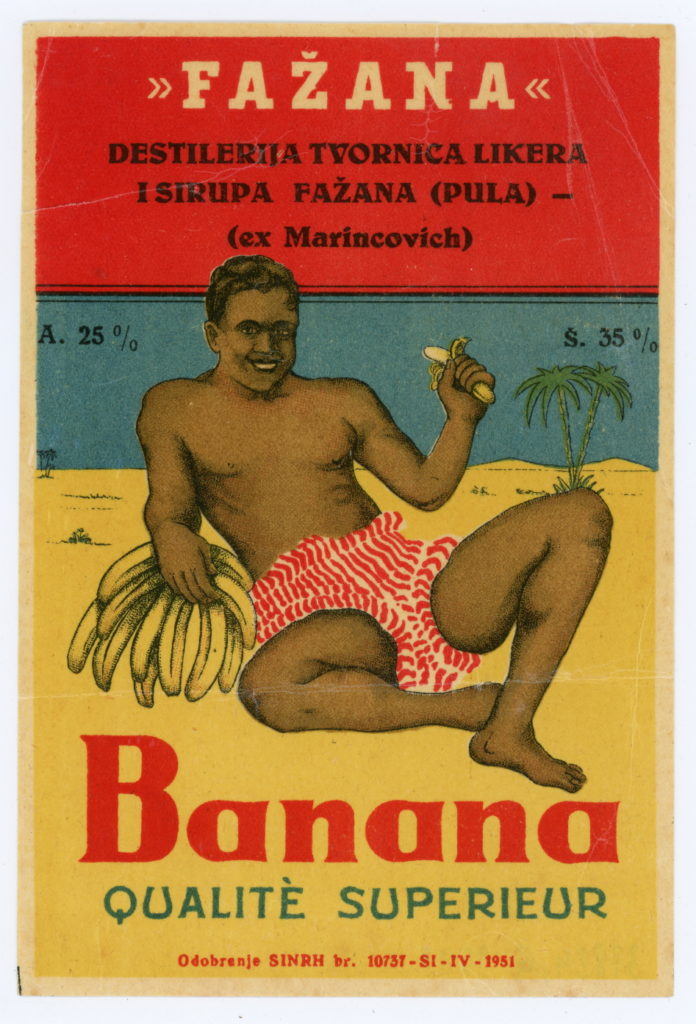

The liquor and soft drinks factory in Fažana had a long tradition of production. Its history began in 1897 when Rodolfo Marincovich opened a liquor factory and distillery called Premiata distileria e fabbrica liquori Fasana. After World War II and the post-war nationalization process, the Marincovich factory became part of the state sector on 12 December 1947 and was renamed Tvornica likera i destilerija/Fabbrica liquori e distileria Fažana. However, initially, the factory did not do well – the company failed to obtain a state loan and the lack of financial resources hampered the factory in its development. In addition, the factory and distillery buildings needed a lot of repairs and improvements to accelerate production, which were unfeasible during a period of financial difficulties. From the end of 1947, the factory was operated by the Marincovich brothers: one brother was the technical director and the other was head of accounting. Their business results were not bad, but remained unsuited to the operating style of state-owned enterprises. In order to eliminate such “irregularities,” on 18 July 1949 the Executive Committee of the District of Pula issued a decision establishing a Districts-level Liquor Manufacturing Company of Fažana, and the official name of the company was Tvornica likera Fažana (the Fažana Liquor Factory). Anton Grbin was appointed director, and held this position up until 1 December 1959 when he was moved to the position of chairman of the board of directors, while at the same time Stefano Moscarda was appointed as acting director. A few months later, Josip Udovčić was appointed as factory director, and day by day the factory stepped up its production and sales of quality products, becoming a recognizable trademark in local and republic-level markets. The increase in production required greater manpower and a bigger and better space than that provided by the old factory. In the mid-fifties, the factory once again changed management and expanded its range of production, therefore changing its name to the Company for the Processing of Agricultural Products and the Production of Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Beverages Fažana (Pula). However, due to negligence and costly management errors, the factory ran into major problems once again and after some time, in 1962, the liquidation process was initiated. After liquidation, the factory resumed regular production, and the following year it was taken over by Badel from Zagreb, which at that time was in the process of taking over several other factories.[2]

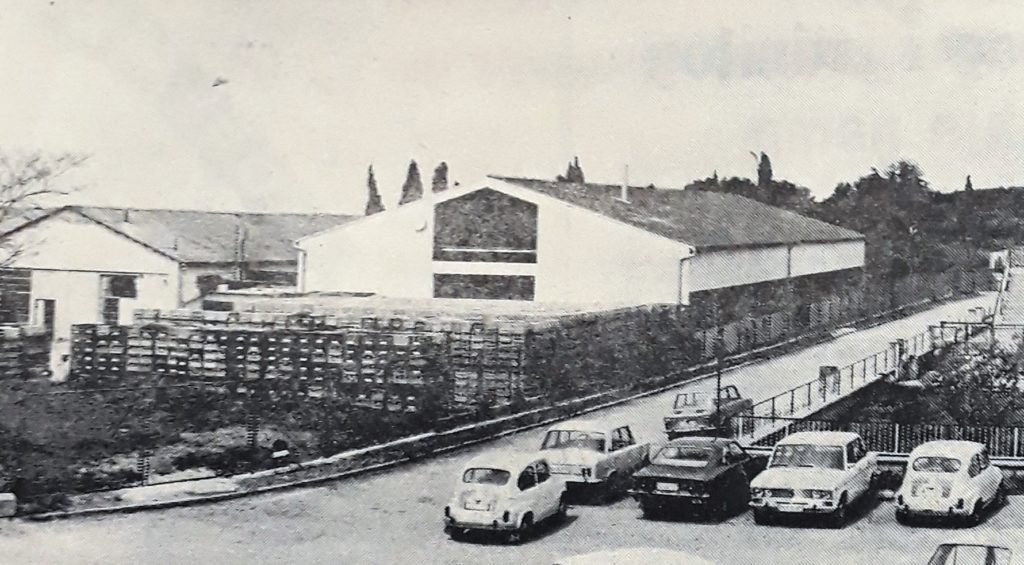

During this Badel integration process, one of the first factories to integrate with Badel was the Fažana factory in 1964. After its integration with Marijan Badel, the Fažana factory sharply increased its own production while increasing the traffic of merchandise rapidly at the same time. These goods were imported into the Istria region from Zagreb-based factories. Within three years of the integration, new capacity-increasing equipment was installed in the Fažana factory worth 90,000,000 old Yugoslav dinars, fully equipping the factory with machines for the production of strong alcoholic drinks, carbonated soft drinks and syrups. Furthermore, in May 1966, a new automatic boiler house was built, which was one of the most modern boilers in Istria at that time. In addition to the automatic line, a semi-automatic bottle washer was installed, in which 0.25 liter bottles for carbonated soft drinks were washed. The plant was able to fill so-called soda water in bottles of various sizes. In a separate room there was a filling line bottling alcoholic beverages and fruit syrups.[3] However, the Fažana collective’s successes were so far very modest. In the second half of the sixties, the Fažana factory did not reach the production norm required of the companies, despite their constantly increasing the average production level. Therefore, in order to create the economic conditions the factory needed, which had been achieved in the other Badel-owned factories, in 1967 the Fažana factory finally gained its own complete production program. In accordance with that program, the necessary equipment for the production of syrups and soft drinks was installed, with clear prospects for the further development of the Badel company in Fažana and with the aim of raising the standard of living. The new production capacities included more technologically advanced equipment and the new soft drink bottling line was of the utmost importance, as the Fažana factory specialized in the production of soft drinks, strong alcoholic beverages in so-called “mini-bottles” and syrups, which were one of the most important factory products. One of the main problems the Fažana factory initially encountered was with the work collective, which mainly consisted of young people who were seasonal workers and often unskilled. This is why the Badel factory in Fažana invested special funds in the training of young workers who – after completing courses for better and more efficient production skills – received appropriate qualifications and working skills.[4]

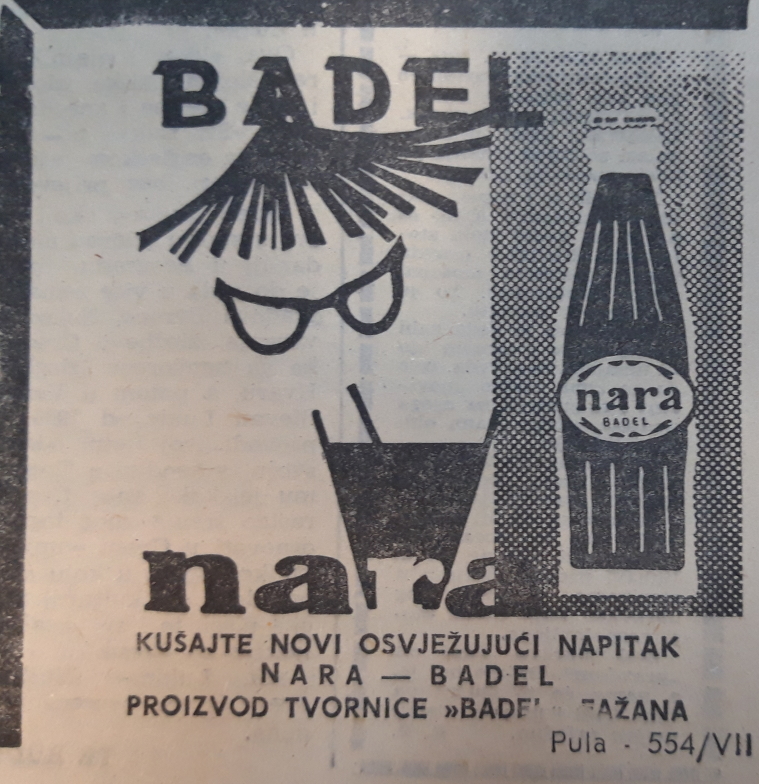

Badel advertisement, Glas Istre, 1971

Badel holiday greetings, Glas Istre, 1971

On the ten-year anniversary of the successful integration of the Fažana factory into Badel, development and success were evident. For example, from 31 employed workers in 1964, the number of employed had increased to 116 workers in 1973 (a fourfold increase). The total revenue rose from 204 million to 5.7 billion of the old Yugoslav dinars (28 times more). The average personal income increased from 30,000 to 205,000 old dinars. As for the material volume, production increased from 15,000 liters of strong alcoholic beverages in 1964 to 760,000 liters in 1973. Syrup production increased from 178,000 liters to 1,132,000 liters, while soft drink production doubled from 1,260,000 units to 2,452,000 units. These results confirmed the business expectations of 1967 and were attained through the better organization of work and through better use of existing capacities. The mid-term development plan, up until 1978, envisaged the construction of a new hall with an area of approximately 1,000 square meters, as well as the construction of an overhang for the packaging of mini-bottles and cardboard boxes, social spaces (canteens, changing rooms, bathrooms and toilets) and an administrative building. At the level of the Pula municipality, in all socio-political organizations and bodies of the municipal assembly, the Badel Fažana factory’s “development path” was stressed as an example of a very successful integration.[5] From the first day of the integration, the Fažana factory acted as an Osnovna organizacija udruženog rada (OOUR – Basic Organization of Associated Labor), because its workers made their income and decisions on the factory’s distribution themselves, as well as decisions on their material and social position, without outside interference. In accordance with the 1974 Constitution and the decisions passed at the 10th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and the Law on Associated Labor (passed in 1976), economic and political power was conferred on workers’ associations. The OOUR became the basis of the system. Workers made decisions about income by themselves, either directly or through their delegates.[6] Consequently, the 1974 Constitutional Amendments reaffirmed the already constituted Basic Organization of Associate Labor that had operated at the Badel Factory in Fažana since 1964.

In the late 1970s, the factory experienced the peak of its modernization. During 1978, the factory had the most modern machinery at its disposal, whose suppliers were the companies Bortolin and Ronchi from Italy. The 1974 plans for the construction of a new production hall with a boiler room, a water-cooling device and a water treatment plant were also achieved. The capacity of the new production hall was four times higher than that of the previous one. The new technology, in addition to greater soft drink production and greater stability of quality, enabled Badel to expand its product range.[7] Moreover, in 1979 the production hall became fully equipped with a new line of soft drinks – Pepsi Cola. Badel and Pepsi Cola have a successful business cooperation since 1967. In that year the Pepsi Cola bottling plant opened in Zagreb, in Vlaška street, offering a new product to the market, alongside the already well-known brands of Cockta and Nara.[8] A Pepsi Cola bottling plant was opened as part of the hall and inaugurated on 11 March 1979, although even before that the factory produced Pepsi Cola, albeit to a much smaller extent. The factory bottled Pepsi Cola in bottles of 0.20 and 1 liter and was the first in Istria to sell these items. The Fažana factory was the eighth largest in Yugoslavia producing Pepsi Cola, and together with the other Badel plant in Borongaj, Zagreb, it completely satisfied the Croatian market.[9] The Fažana factory’s OOUR concluded a new contract with Pepsi Cola a few years later, in 1986, and on that basis the factory in Fažana received a complete production line for bottling soft drinks. The nature of this cooperation was under the technical and technological purview of the Fažana OOUR, designed with the intention of increasing production and meeting the growing demand for these sorts of drinks in the Istrian market.[10]

After the new hall’s construction, Badel Fažana became the largest producer of soft drinks in Istria. Imported equipment was installed in the new hall, which enabled the production increase and modernization. In addition to the already traditional Nara and Inca Tonic Water, the new hall was also equipped for bottling other soft drinks that were not previously in the production program.[11] The technology installed in the new hall increased its capacity by two and a half times. More modern machines allowed the quality of all beverages to remain more consistent, which helped to improve the quality and find new consumers. In the late 1970s, due to the enforcement of stricter traffic rules, the production of strong drinks was reduced, and sales of so-called mini-bottles of strong alcoholic beverages decreased, unlike the situation in the late 1960s and early 1970s. However, one of the main products of the Fažana OOUR was fruit syrups. At the Fažana factory, the syrups were prepared in special devices, in the so-called “evaporation station,” or as it was popularly called by Fažana’s Badel workers – “cooking plant.”[12] To meet the market requirements for the production of syrup, in 1977 the factory bought the most modern production line for filling syrups with a capacity of 4,000 liter bottles per hour, from the already mentioned Italian company Ronchi.[13] Soon after, great attention was paid to the export of manufactured goods, and in 1979 the factory exported drinks valued at around two million dinars to the Federal Republic of Germany.[14]

The Badel factory in Fažana often participated in various social activities. Very often, on the pages of the daily newspaper Glas Istre, various sweepstakes could be found, in which many Badel products could be won. In addition, in the summer of 1974, the factory hosted youths from the Badel facility in Šibenik, who came to visit the Badel factory in Fažana, where they learned about the establishment of the Fažana factory and the plans for new lines, the expansion of production and the construction of new facilities. The youths from the Badel-Vinoprodukt plant from Šibenik were students at the Fažana Youth School of Politics, where they attended seminars on socio-economic relations, in order to train themselves, together with other students, for everyday socio-political work. Furthermore, in the municipality of Pula in 1981, the action “NNNI – 81” (an abbreviation of Ništa nas ne smije iznenaditi, which means: Nothing Should Surprise Us) was held and as part of the action, a methods-demonstration exercise was held at the Fažana Local Community Center and at the Badel Fažana OOUR. This action was attended by members of all socio-political structures from the Pula municipality. The Badel Fažana OOUR made a significant contribution to this exercise. In addition, first-aid exercises, emergency sheltering, industrial fire-fighting and rescue-from-debris exercises were held at the factory premises.[15] Some workers were rewarded for their services with apartments in the newly built settlement in Fažana. Such a decision was a result of the Marijan Badel branch of the League of Communists, which endorsed the Committee’s recommendations of 28 November 1972 concerning the use by members of the collective of various types of enterprise services, such as workshop services, transportation services and a housing allocation.[16] After Badel showed interest in apartments newly built near the football field in 1977, they purchased 18 of the apartments for their workers, together with the Glass Factory, the police (RSUP) resort of Valbandon and the Brijuni Islands Authority. The entire settlement had about a hundred new apartments at that point.[17]

In the early 1980s, Badel continued to record positive results. The products of this small work collective in Fažana, consisting of a total of 120 workers in 1981, continued to be marketed throughout the entire Croatian market, as well as in Serbia, Bosnia & Herzegovina and Macedonia. The main products remained unchanged – soft drinks and various syrups – while the mini-packs of alcoholic beverages were marketed even in Western markets, achieving sales success and better market placement than in the second half of the 1970s. Thanks to the factory’s modernization during the second half of the 1970s, the operating conditions at the plant were indeed satisfactory: the entire premises were air-conditioned and the staff was trained for work internally. During the summer season, the work collective also employed an additional 30 workers through the Youth Cooperative. Unlike the aforementioned seasonal workers, who also worked through the Youth Cooperative in the early 1970s, in the 1980s the seasonal workers were appointed frequently, but were also trained for every job. They worked in four shifts and all workers from the first shifts were provided with meals, which they received from the children’s resort JDRC Puntižela. The price of the meal was ten dinars, and the workers also received a free Badel soft drink. Workers who worked on the other shifts had the right to a cold meal.

However, Badel’s peak in the late seventies ended with a crisis in the eighties that affected all the Badel plants, including the Fažana OOUR. The economic crisis affected all branches of industry and this branch was not spared. Due to the high interest rates in the eighties, Badel was no longer able to realize the desired investment policy. The problems that the work collective faced related to the procurement of raw materials. Another problem they encountered was the procurement of packaging (bottles), which did not arrive in sufficient quantities. Bad business management started in 1983, when production was down 2% compared with 1982, and exceptional failures occurred in the Fažana OOUR specifically, mainly caused by a lack of raw materials. The decline in purchasing power of the population over the following years was also reflected in the Badel products’ sales figures, and the general decline in societal living standards had an impact on the Badel business.[18] Although it was still operating on the basis of four shifts, due to the crisis, the factory did not meet the expected physical volume of production. Carbonated drinks were the most sought after and not enough were produced, despite around 100,000 bottles being produced daily. Pepsi, lemon, and orange concentrates were not available as in previous years due to foreign currency shortage. Moreover, during June and July 1983, the factory did not produce syrups due to a lack of sugar.

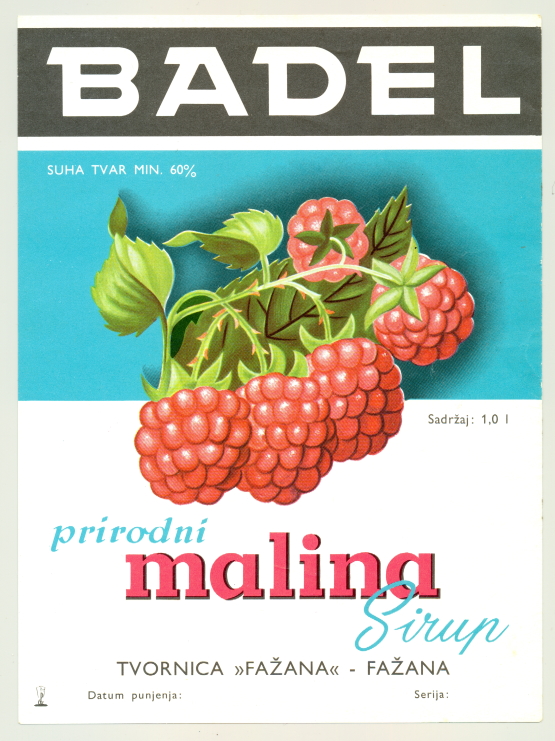

Raspberry syrup, 1970s (PPMI)

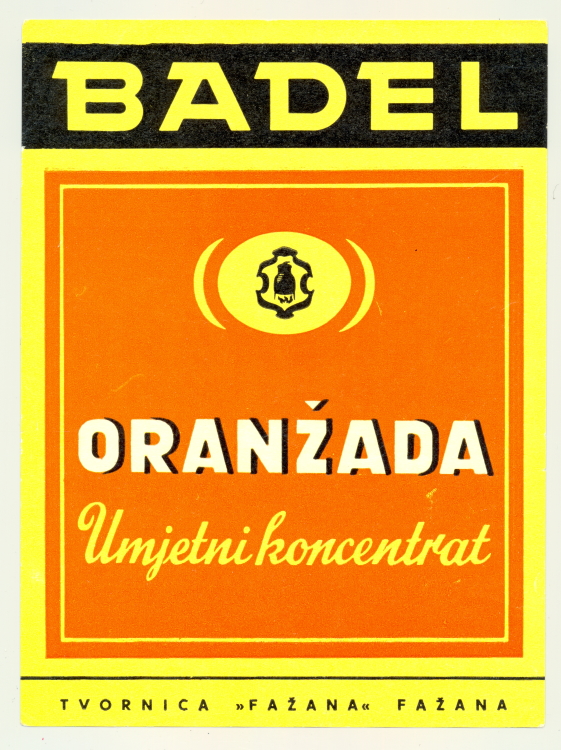

Orange concentrate, 1970s (PPMI)

In order to minimize the shortcomings caused by the foreign currency embargo, the factory management continued to invest in the machinery’s modernization. The factory had a modern syrup-making room, comprised of three vacuum evaporators that were needed to increase production threefold. There was also a laboratory in the factory where products intended for the market were analyzed.[19] However, the machinery modernization could not compensate for the emerging demand. Since the factory did not fully realize the planned development program in the first half of the 1980s, the Badel factory in Fažana was part of the Plan for Socio-Economic Development of the Municipality of Pula for the period from 1986 to 1990. According to the five-year plan, the production of alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages had to be multiplied in quantity several times over. The plant also had to continue modernizing and expanding its existing facilities. The plan also included the construction of business premises, worth 329 million dinars.[20]

The factory’s planned development was not implemented

again. Bad business results at the OOUR in Fažana continued with losses through

all the years up until 1989. In order to combat the crisis in all the Badel

plants, from 1 January 1990, RO Badel started to operate through four united socially

owned companies. Significantly better financial results were expected of such a

company. In addition, as of 1 January 1990, the Badel-BAP Company was formed by

merging the OOUR Factory of Soft Drinks and Juices Borongaj and the OOUR

Factory of Alcoholic and Soft Drinks and Syrups Fažana. One of the essential

prerequisites for the new company’s normal functioning was the setting up and

implementation of a unique and functional organization of work and business, as

well as the creation of a standardized and optimal product range program.[21] The

fact is that both of the OOURs, Borongaj and Fažana, had great business

autonomy by 1990, and in many elements were already existing as separate

companies and so a merger model was neither a rational nor an effective

solution. Consequently, the factory became a joint stock company and each

worker could buy shares to the amount of DM 20,000. However, due to the

socio-political circumstances of 1991 – the breakup of Yugoslavia, high unemployment,

the state of war – small shareholders sold their shares so they could survive.[22] Zagreb’s

neglect of the Fažana facility, and political interference in business and

management, led to the factory’s closure in the late 1990s. The Fažana case of

the Badel Factory is a classic example of a “failed industry” in the 1990s; an

industry that did not survive the transition and privatization. The town that

once had a strong industry, whose products were marketed beyond the borders of

Yugoslavia, does not even have one factory today. Almost all workers lost their

jobs, and the town gradually began to adapt to tourism. Today all of Fažana’s

income is based solely on tourism, while at the same time, its rich industrial

past and its heritage have been forgotten.

Sara Žerić is completing her MA studies in history at the Juraj Dobrila University of Pula in 2020, and she is interested in social history of Yugoslavia in socialism, especially modernisation and everyday life.

[1] Besides the liquor and soft drinks factory Badel, Fažana’s industry was also comprised of a branch of the glass factory Boris Kidrič from Pula, which had been on the site of the former Crvena zvijezda (Red Star) shipyard since the early 1970s.

[2] Moscarda, Giancarlo, „Gospodarstvo Fažane u 20. stoljeću“, Fažanski libar, ed. Mirko Urošević, Općina Fažana, Fažana, 2007, 181-82.

[3] „Ulaganja u postrojenja već daju veći dohodak“, Badel, 2, June 1967, 4.

[4] „Mladi ‘Vinarije’ u Istri“, Badelov list, 7.10.1974, 6.

[5] „Amandmanska integracije prije deset godina“, Badelov list, 2.5.1974, 5.

[6] Sabolić, Kruno, ed., Badel 1862: 140 godina postojanja, Badel 1862 d.d, Zagreb, 2002, 76.

[7] „Modernizacija fažanskog Badela“, Glas Istre, 07.03.1978, 5.

[8] Sabolić, 65.

[9] „Svečano otvorena nova punionica Pepsi Cole“, Badel, 4/5, May 1979, 9.

[10] „Nova linija za pepsi colu“, Badel, 3.4.1986, 3.

[11] „Badel gradi novu halu“, Glas Istre, 07.10.1975, 4.

[12] „Kišno ljeto skratilo „Badelov“ plan“, Glas Istre, 11.08.1976, 4.

[13] „Uskoro više pića i sirupa“, Glas Istre, 13.10.1977, 4.

[14] „Badel Fažana povećava proizvodnju“, Glas Istre, 09.08.1979, 4.

[15] „Akcija ‘NNNI-81’ i u Fažani“, Badel, 6.6.1981, 2.

[16] „Konferencija Stalne konferencije SK poduzeća ‚Marijan Badel‘“, Badelov list, 4.6.1977, 4.

[17] „Stotinu novih stanova“, Glas Istre, 17.10.1977, 4.

[18] „Vjerujemo u snagu Badelovih proizvoda“, Badel, 8.8.1984, 2.

[19] „Proizvodnja pića u četiri smjene“, Glas Istre, 01.08.1983, 5.

[20] Plan društvenog-ekonomskog razvoja općine Pula za razdoblje od 1986. do 1990. godine, Studij Ekonomije i turizma „Dr. Mijo Mirković“, Pula, 1986, 27.

[21] „U našoj braniši smo među bolje organiziranim poduzećima“, Badel, 1.1.1990, 5.

[22] Moscarda, 182.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Badel, Zagreb

Badelov list, Zagreb

Glas Istre, Pula

Literature

Moscarda, Giancarlo, „Gospodarstvo Fažane u 20. stoljeću“, Fažanski libar, ed. Mirko Urošević, Općina Fažana, Fažana, 2007, 177-95.

Plan društvenog-ekonomskog razvoja općine Pula za razdoblje od 1986. do 1990. godine, Studij Ekonomije i turizma „Dr. Mijo Mirković“, Pula, 1986.

Sabolić, Kruno, ed., Badel 1862: 140 godina postojanja, Badel 1862 d.d, Zagreb, 2002.