Katarina lies on the right-hand side of the bay of Pula. A military complex abandoned after Yugoslavia, it is replete with disintegrating buildings and thick undergrowth, a place where people cycle, make barbecues, walk dogs, smoke joints, socialize in the warm summer evenings, and attend music concerts. The area has been deliberately left to its own devices, the Yugoslav and Austro-Hungarian era barracks stripped of their contents and graffitied. While the land has been purchased and a repurposing is planned, progress is slow. The discovery of mines within the grounds during 2018 has slowed things down even further. Let’s take a walk down there.

The main entry point is down past the railway station by the shore, crossing a rickety footbridge.

This entry point is home to thick undergrowth and dilapidated buildings.

People can often be seen walking their dogs around the Katarina area and complex. One of Katarina’s defining features is the presence of past material infrastructure. The rickety bridge we passed earlier gives away the presence of train tracks, and these are carved into the ground at multiple points. They simply form part of the backdrop, little emphasized and left in a state of disrepair.

A little further down, an open-plan area can be found. Each summer an open-air festival takes place here. While the space was earlier open and the barracks could be visited, the discovery of mines means that the area has been closed off. Before it was possible to directly enter the barracks themselves, full of debris and old military issue boots in piles, alongside the unmistakeable and all-encompassing musty smell of damp. Travelling yet further down, you can reach the island “Sveta Katarina” itself, earlier host to barracks and a training centre for marines. You could reach it by bike from the city centre and even go out further to the barrier marking the harbour wall, before the mines closure.

The barracks and decay mark a strong contrast with the enormity of the (previously-)active shipyard. The so-called “otok“ (the island; below) can be seen from the shore. This brings us neatly on to the topic of rumours.

Rumours and deliberate decay?

A variety of rumours circulate concerning Katarina, both in relation to its past and possible future. There are rumours of unexploded munitions on the seabed, including a WW2 bomb and even a secret underground cave, which formed part of the military installation and provided an entrance for submarines.

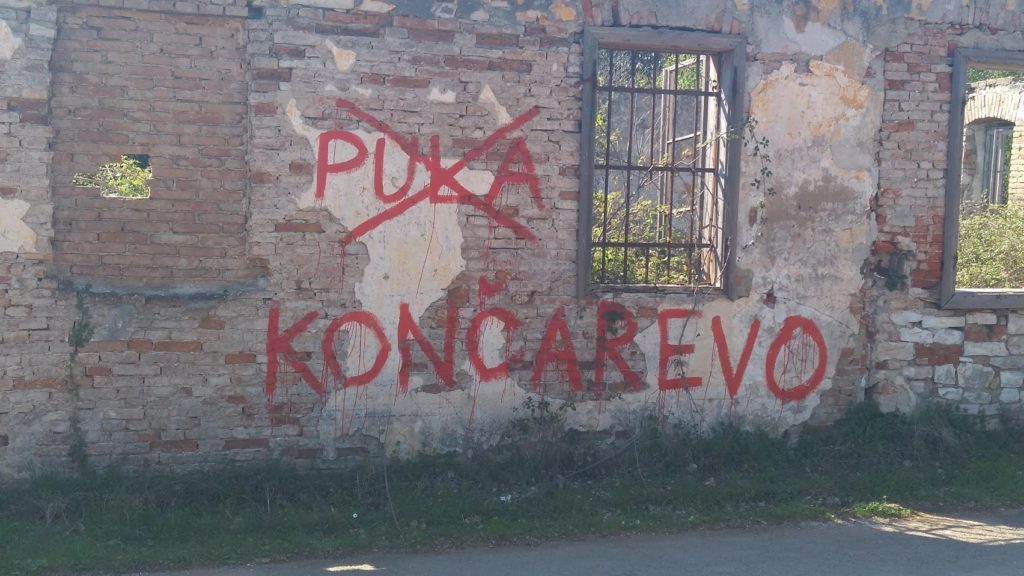

As concerns the future, the reasons why Katarina is left the way it is, and why the repurposing has taken so longer are dissected, along with the intentions of the Croatian tycoon “Danko Končar”, who own the concession to the territory, and was named strategic partner for Uljanik Shipyard in 2018, a strange proposition given the gap between a vision of Pula as a centre of the shipbuilding industry and Končar’s wish to build a luxury marina and hotels in the now-derelict barracks of Katarina. These intentions have provoked a counter-reaction:

While the military past has been pushed to one side in the case of Katarina, and the barracks form parts of the cityscape, especially around the neighbourhood of šijana, the large building of Rojc continues to be used by an incredibly wide variety of civil society and other social groups, ranging from music and exercise groups, to LGBTQ groups, punks, football fan associations, war veterans’ groups, co-working spaces and so on, all under one roof. The present-day Pula, at least from the position of the city authorities, is overwhelmingly focused on tourism. This linked to one account I came across of Pula’s development. The argument was that Pula had not developed “organically” as a city, its growth having been stunted by the two imposing presences of the military and heavy industry. This was especially the case with the military influence, due to its secrecy and separateness from civilian everyday life. Stunted in this way, Pula needs pushing out a rut of its own creating. This line of reasoning justifies the mass expansion of tourism, and if applied to Uljanik, the downsizing of its industrial presence in the city.

Katarina might be scruffy and on the margins, but it remains part of many people’s everyday lives, while material references to the military past are part and parcel of the cityscape, in and through the use of spaces such as Rojc.

Andrew Hodges is a social anthropologist and a researcher at the Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies in Regensburg, Germany.